They say old songs are like memories, imprinted in your mind and heart forever. Whenever you listen to them, the lyrics, beat and melody transport you back to when you first heard the song. While the current generation of musicians is pushing the boundaries and creating diverse tunes, nothing beats the iconic songs many of us grew up listening to. Now, during this time of lockdown, many of us are relying on music to pass time—what’s better than to relive old memories through some iconic songs? Here, we bring you five legendary Nepali songs of yesteryear, to tell you their stories and the memories of the artists involved in these songs, who never thought their sonic art would become timeless.

Rajamati Kumati by Prem Dhoj Pradhan

What’s one particular Nepal Bhasa song everyone knows? From being played during the guard of honour of Prime Minister Junga Bahadur Rana, during his 1850 state visit to England, to being played during cultural programmes even today, the classical ‘Rajamati Kumati’ is timeless. Composed in the 19th century, the person behind its creation remains unknown. However, when the song was recorded in 1963, the ballad found a new voice with legendary singer Prem Dhoj Pradhan.

“It was the motivation from my friends and community members that led me to travel all over to Calcutta (Kolkata) to record this song,” says Pradhan. While he had been performing the song in his own style live on stage and events, the need to document the recording of the song was significant for Newa culture, he says “By making the song travel to many houses, I felt that it would preserve and promote the Newa culture,” says the 84-year-old musician.

However, it wasn’t easy for Pradhan to record the song. Travelling miles from his homeland, in the Kolkata recording studio, he didn’t have an artist who could play madal, an important instrument required for the song. “I took my own madal and taught a musician who could play tabla. We couldn’t afford many re-takes so whenever we performed we gave our best,” says Pradhan, who initially recorded 200 copies of the song and later sold a few to Radio Nepal, who played the song regularly.

Pradhan also sang the song for the 1995 Nepal Bhasa movie, ‘Rajamati’, based on the story of the same ballad that made the song reach a new height in terms of popularity and love.

Mai Chori Sundari, by Bharati Upadhya

Singing came naturally to Bharati Upadhya. Raised in a family of singers, Upadhya was given the famous ‘Mai Chori Sundari’ by her mother, who had composed it for her.

“I instantly fell in love with the song, as I was touched by the fact my mother composed a song dedicated to me, her youngest daughter,” says Upadhya.

As she was living in Assam back then, she instantly went to the studio and recorded the song. Although the local radio station played the song, it got exposure only when Upadhya recorded it in Nepal in 1974, after she moved here. Radio Nepal widened its reach, and the song was a hit.

While she has a vivid memory of the musicians and technicians involved in the song, Upadhya says recording the song was a feat in itself. “Back then we had to do live-recording. So even if a single person made a small mistake, we had to redo it from the beginning. We faced the same while recording the song but at the end, everything was worth it,” says Upadhya.

Upadhya believes this song carved her identity. “I have sung so many songs, but most people remember this song from my discography. It’s less a song, but more of my identity now,” she says.

Parelima, by 1974 AD

Since their origin in 1994, the veteran Nepali rock band has been known for bringing people together with their music. ‘Parelima’ is still one of the go-to songs played and strummed during any get-together. Even 22 years since the song’s making, ‘Parelima’ has been making memories for everyone; its nostalgia is indelible.

Manoj Kumar KC, the lead guitarist and keyboard player of the band, strummed the melody one afternoon, and showed his tune and rough lyrics to Phiroj Shyangden and Nirakar Yakthumba, after he had joined the group officially.

“The idea was to create something similar to Extreme’s ‘More Than Words’; I was really inspired by the song and started working on the pattern, melody, and lyrics to create something along the same line,” he says.

‘Parelima’ came out in 1998 and was part of their hit album ‘Samjhi Baschu’. The song was acoustic and thus imbued even more simplicity, tending to the more profound emotion of wanting to be loved. “That song is still one of the most loved songs by people, and I think it’s because of its simplicity; the chords and the beat are effortless and even the words are very subtle,” says Phiroj Shyangden, who sang the song. “Anyone can play and sing that song easily, and its accessibility, I think is what makes it special.”

But KC also believes the song’s undying popularity is a result of the band exploring something new at a time when rock music was more palatable. “We always remember things that are experimental,” he says. “But ‘Parelima’ was also able to travel in parallel with people’s journey, and I guess that is why the song is special.”

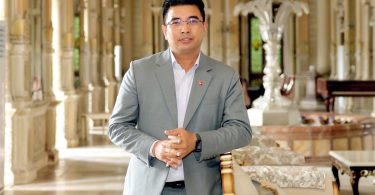

Maya Ko Dori Le, by Deepak Bajracharya

When rockstar Deepak Bajracharya first listened to ‘Maya Ko Dori Le’, he wasn’t convinced to lend the song his voice. “I thought the song wasn’t made for me,” says Bajracharya, who was ruling the music industry with back to back hit songs for almost a decade from his debut song, ‘Kali Kali Hisi Pareki’.

However, when the song was arranged with Latin beats, Bajracharya decided to try it. “When James Pradhan [who arranged the song that was composed by Kamal Man Singh] made me listen to the new version, which had a Latin touch to it, I got interested. We had just returned from a party and he had asked me when I wanted to sing it. I got excited and told him I was ready to sing it then,” says Bajracharya, who placed this song in his fifth album, ‘Asar’, released in 2002.

Like the song, the music video became so popular for introducing salsa to Nepali viewers. “Captain Vijaya Lama suggested I should incorporate salsa in the video, as my song had a Latin flavour to it. Back then his friend Diego, a salsa professor, was in Kathmandu and we decided to go ahead with it,” says Bajracharya, who has had hits with songs such as ‘Oh Amira’, ‘Ritu’, ‘Allare’ and more recently, ‘Man Magan’.

While he didn’t initially have plans to be in the video, he later decided to appear on the screen, moving his legs as well.

Mathi Mathi Sailunge Ma, by Kunti Moktan

Kunti Moktan’s ‘Mathi Mathi Sailunge Ma’ is an evergreen tune for all Nepalis. It continues to be an anthem for Nepalis besides Moktan’s songs like ‘Choli Ramro Palpali Dhaka Ko’ and ‘Laligurans Ajambari’.

However, the song initially had struggled to get a proper release, says Moktan. ‘Mathi Mathi Sailunge Ma’ played on the beat of Tamang Selo, and also used drums, electric guitar and piano. It was a mixture of pop and traditional Nepali folk beat, which made it something that didn’t exist in the market during the early ’90s. “When we approached record companies to make cassettes, many rejected the song saying that it was not what they were looking for,” says singer Moktan.

But a few years after the song’s release it won awards for two years straight. And, to this day, it remains the song Moktan is most-requested during her shows.

“The song picked up only a few years after its release, but people really loved it,” says Moktan. ‘Mathi Mathi Sailunge’ was composed by Sila Bahadur Moktan, Moktan’s husband, and written by Shrawan Mukarung. But even while all this happened lyricist Mukarung had no idea the song had been released even after a few years of its debut.

“I wrote that song way back in time, when I was living like a hippy. I was probably 25 years old. One late night I had written that song on the cover of Yak Cigarettes, after writing a poem just because I was not over with my writing that day,” he says. The next day Mukarung carried the piece of paper in his pocket as he took a stroll around one of his neighbourhood’s temples. And as he was returning, he ran into Kunti Moktan and her husband who were riding by. Moktan had jokingly complained, “you never make songs for me,” Mukarung replied with the cigarette packet in his pocket, the soon-to-be famous verses inked on its face.

It was only years later, he heard his song for the first time on the radio. “In those days, there was no means of communication. I had no idea. I had already even forgotten the song,” he says.